After their silent and momentary seizure of five municipal plazas on December 21, the Zapatistas issued a new communiqué (in Spanish or English). In sum, it describes how they will continue consolidating their “other way of doing politics.” Among their “next steps,” says the text, will be a renewed push toward national and international political alliances, organizing, and solidarity with indigenous groups and those who struggle “from below and to the left.” The communiqué reiterates their total rejection of Mexico’s institutions and its political class—from right to left—heralding how Zapatista communities have successfully territorialized their autonomous forms of indigenous government. Proof of this, according to the text, is the much higher standard of living enjoyed by Zapatista territories compared to those overrun by the Mexican government and its various political parties.

After their silent and momentary seizure of five municipal plazas on December 21, the Zapatistas issued a new communiqué (in Spanish or English). In sum, it describes how they will continue consolidating their “other way of doing politics.” Among their “next steps,” says the text, will be a renewed push toward national and international political alliances, organizing, and solidarity with indigenous groups and those who struggle “from below and to the left.” The communiqué reiterates their total rejection of Mexico’s institutions and its political class—from right to left—heralding how Zapatista communities have successfully territorialized their autonomous forms of indigenous government. Proof of this, according to the text, is the much higher standard of living enjoyed by Zapatista territories compared to those overrun by the Mexican government and its various political parties.

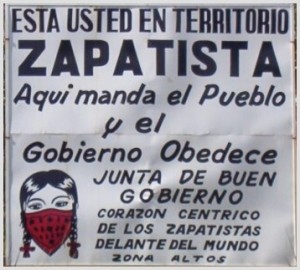

With the long-ruling PRI now back in power after a 12-year absence, the Zapatistas reconfirmed their rejection of electoral politics. In 2006, they had come under harsh criticism from leftist parties and intellectuals for rejecting the presidential run of a left-leaning candidate. “Six years later, two things are clear,” says the communiqué. “They [the institutional left] don’t need us to fail; we don’t need them to survive.” The text also called on the state to recognize that “a new form of social life has bloomed in Zapatista Territory, Chiapas, Mexico.”

The communiqué reinforced for me an idea I have brewing for a text I’m thinking about that will describe—in a survey or a case study, I’m not sure which—how Latin American social movements talk about and conceive “territory.” In formulaic terms, it’s sort of a combination between or conflation of what geographers have named territoriality, autogestion, and the production of space. In an older post on “Territory and Autogestion,” I wrote:

My point is that territory and autogestion have become conflated in the praxis and parlance of Latin America’s most dynamic social movements, which I’m writing about in admittedly general terms. But this gets even more interesting when we remember that the understanding of autogestion held by Lefebvre (certainly) and Latin American movements (usually) is anti-statist. Indeed, Lefebvre’s vision of democratic socialism is based on this anti-statist notion of autogestion. Many Latin American movements engage a praxis of territory in this same sort of anti-statist fashion—a tendency partly dulled by Latin America’s leftward statist tilt….

When radical social movements in Latin America think, talk, and act in terms of “territory,” which they do constantly, they dialectically marry autogestion and the kind of [overt] politicization of space described by Lefebvre. In their praxis, territory is a space that is autogestionado.

But what happens if we avoid shooting the praxis of groups like the Zapatistas through the radical canons of geographical theory (Marxist or otherwise)? For my own research on communities organizing against Colombia’s armed conflict, this would mean exploring their often-repeated statement, “Territory is life.” What happens when we take the overtly political geographical praxis of subaltern political actors seriously on its own—that is, as itself a form of radical geographical theorizing? What’s lost (if anything) and what’s gained?

Chris Hesketh writing on Adam Morton’s blog summarizes his new Latin American Perspectives article on the continuing relevance of Zapatista struggles. Much more elaborately, he makes a similar point. He writes: