What’s flat, has two legs, and is capable of stirring international intrigue on the high seas? If you’re thinking “unmanned wave-powered ocean robots,” then you’re close, but (sadly) wrong. No, I’m thinking of the 120-foot by 50-foot platform seven miles off the English coast proudly named the Principality of Sealand. The former World War II-era anti-aircraft fortress, once called Roughs Tower, has made waves in the news recently. First, the NY Times’ cartography blog profiled Sealand’s surprising history, calling it the world’s most successful micronation. But what caught my attention were the unfounded rumors (fanned by Fox News) that WikiLeaks was considering a plan to station its servers on Sealand. It turns out that the hope of turning Sealand into an “off-shore” data hub has been tried before. As reported by Wired years ago, the original idea by a company named HavenCo was to make the micronation a “fat-pipe Internet server farm and global networking hub that combines the spicier elements of a Carribean tax shelter, Cryptonomicon, and 007.” Like most things Sealand, the plan to turn the platform into The Caimans of the Internet was a total disaster. James Grimmelmann, a law professor at NYU, recounts the episode at ArsTechnica.

What’s flat, has two legs, and is capable of stirring international intrigue on the high seas? If you’re thinking “unmanned wave-powered ocean robots,” then you’re close, but (sadly) wrong. No, I’m thinking of the 120-foot by 50-foot platform seven miles off the English coast proudly named the Principality of Sealand. The former World War II-era anti-aircraft fortress, once called Roughs Tower, has made waves in the news recently. First, the NY Times’ cartography blog profiled Sealand’s surprising history, calling it the world’s most successful micronation. But what caught my attention were the unfounded rumors (fanned by Fox News) that WikiLeaks was considering a plan to station its servers on Sealand. It turns out that the hope of turning Sealand into an “off-shore” data hub has been tried before. As reported by Wired years ago, the original idea by a company named HavenCo was to make the micronation a “fat-pipe Internet server farm and global networking hub that combines the spicier elements of a Carribean tax shelter, Cryptonomicon, and 007.” Like most things Sealand, the plan to turn the platform into The Caimans of the Internet was a total disaster. James Grimmelmann, a law professor at NYU, recounts the episode at ArsTechnica.

Grimmelmann’s article is a summary of longer essay he published in the Illinois Law Review (PDF) that discusses Sealand and the rule of law in the Internet Age. I haven’t read the longer piece, but it’s abstract is enticing (excerpt):

Grimmelmann’s article is a summary of longer essay he published in the Illinois Law Review (PDF) that discusses Sealand and the rule of law in the Internet Age. I haven’t read the longer piece, but it’s abstract is enticing (excerpt):

The story itself is fascinating enough: it includes pirate radio, shotguns, rampant copyright infringement, a Red Bull skateboarding special, perpetual motion machines, and the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of State. But its implications for the rule of law are even more remarkable. Previous scholars have seen HavenCo as a straightforward challenge to the rule of law: by threatening to undermine national authority, HavenCo was opposed to all law. As the fuller history shows, this story is too simplistic. HavenCo also depended on international law to recognize and protect Sealand, and on Sealand law to protect it from Sealand itself. Where others have seen HavenCo’s failure as the triumph of traditional regulatory authorities over HavenCo, this Article argues that in a very real sense, HavenCo failed not from too much law but from too little. The “law” that was supposed to keep HavenCo safe was law only in a thin, formalistic sense, disconnected from the human institutions that make and enforce law. But without those institutions, law does not work, as HavenCo discovered.

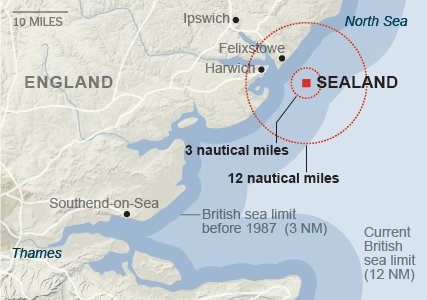

The fort got its countercultural upstart when pirate radio broadcasters set up shop there in the 1960s to escape state regulations. One of them, Roy Bates, declared himself ruler of the Principality of Sealand. In a firearms case against Bates, English courts declared they had no legal authority over the platform because it stood beyond the legal reach of the country’s sovereignty, which at the time was three nautical miles—it was extended to 12 in 1987. This was the first in a series of moves by foreign powers that helped shore-up Sealand’s sovereign claim over the rusting structure. He even managed to fight off a coup in 1978 hatched by a German lawyer. (Bates regained the throne in an early morning helicopter raid.) In 2000, approached by HavenCo, Sealand hoped to cash-in on the dot-com boom. Grimmelmann explains the partners had high hopes for the venture:

Online casinos, subpoena-proof corporate records, good old-fashioned pornography—HavenCo would host it all [on Sealand], safely beyond the reach of any other country’s courts. The company launched to massive press coverage (including a cover story in Wired), promising unfettered free speech to the masses while extending a raised middle finger to censors and control freaks around the world.

HavenCo began shipping in servers and beefing up the platform’s infrastructure. But the venture never really got off the ground. It puttered with about 12 clients and a sorry set of servers. HavenCo’s founder, Ryan Lackey, and the Bates family never got along. Sealand’s authorities say Lackey “was out of control” and “became doctor evil in his lair.” Meanwhile, Lackey accuses Sealand from backing out of the deal, refusing to host a pirated video-streaming service.

HavenCo began shipping in servers and beefing up the platform’s infrastructure. But the venture never really got off the ground. It puttered with about 12 clients and a sorry set of servers. HavenCo’s founder, Ryan Lackey, and the Bates family never got along. Sealand’s authorities say Lackey “was out of control” and “became doctor evil in his lair.” Meanwhile, Lackey accuses Sealand from backing out of the deal, refusing to host a pirated video-streaming service.

Territory, law, illegality, space, the sea, piracy, outlaws… all things of deep interest to this blog. I’ll leave it at that…

P.s. Still Internet-less over here thanks to what Hannah Arendt described as the cruelest regime of all: an incompetent and unaccountable bureaucratic morass (aka my telecommunication company).

Pingback: The FBI Almost Seized My Emails | Territorial Masquerades

Pingback: Sea Property & Exclusive Economic Zones | Territorial Masquerades