Wood, Elisabeth J. 2003. Insurgent Collective Action and Civil War in El Salvador. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wood, Elisabeth J. 2003. Insurgent Collective Action and Civil War in El Salvador. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Elisabeth Jean Wood’s book explores why some Salvadoran peasants decided to collectively thrust themselves toward that country’s insurgency in the 1970s-1990s. Through a series of subnational, ethnographic case studies conducted over several years and oral histories, she finds three main reasons: participation, defiance, and the pleasures of agency. As for the latter, she means “the positive affect associated with self-determination, autonomy, self-esteem, efficacy, and pride that come from the successful assertion of intention” (235). Her account undermines rational-actor theories of collective action based on material incentives and gains. Far from material benefits, Salvadorans that supported or actively participated in guerrilla groups faced extraordinarily high risks without any foreseeable material gains.

Insurgent campesinos are the focus of her study—i.e., poor, rural civilians that supported the rebel groups in one way or another. Campesinos were drawn into and created networks whose “values, beliefs, social norms, and political identities” outweighed the “risk of disappearance, torture, and death” (15). Wood’s book explains how this came to be.

The mobilization of insurgent campesinos, in the end, did achieve some concrete, material gains; in a sense, they achieved a significant agrarian reform from below. But underlying these gains was a much more important and perhaps more-lasting change: the creation of a new political culture whose legacy was to instill “new values, norms, practices, beliefs, and memories tat comprised a new political identity and culture among insurgent supporters” (18).

Wood also finds substantial of path-dependencies for explaining why people join the insurgency, as auxiliaries or otherwise. The path-dependency is strongly tied to local history; that is, whether the locale in question had a history of activism and/or whether it was subject to the initial violence of one particular group. Proximity to insurgent forces is also a key factor in this path-dependency. An important factor determining insurgent support for many campesinos was the political worldview activated by liberation theology and the grassroots organizing of lay catechists. “The guerrilla organizations shaped campesinos’ understandings of liberationist teachings through their ideological work, interpreting state violence as making armed insurgency necessary if liberationist aspirations were to be realized” (120).

Wood’s evidence indicates:

The most important themes in interviews with campesinos who support the insurgency – resentment at the social conditions before the war, aspirations for a more just social and economic order, moral outrage at the repression that followed mobilization, and pride in the achievements of the insurgency – are muted or absent in the interviews with campesinos who did not support the insurgency. (213)

One of the most important factors of all was the brutal violence of counterinsurgency, driving many peasants in the arms of guerrillas. “Repression forged insurgency because it reinforced the framing of the government as profoundly unjust authority, an ongoing demonstration constantly interpreted as such by insurgent organizers” (120). Indeed, Wood’s emphasis is on insurgent campesinos’ moral and political convictions as the main motivators for stepping across the proverbial “line” toward supporting armed insurrection. It was this campesino support that made it possible for the FMLN guerrillas to drive the government toward a stalemate, along with attendant forms of dual sovereignty (135).

Farming cooperatives became a key source of political mobilization—mainly, by the Frente but by the government’s counterinsurgency efforts as well. The FMLN consciously sought to spread its military and political strategies across the combatant-civilian divide. “Overlapping networks of military and political cadres and militant campesinos organized in insurgent as well as reform cooperatives, campesino federations, nongovernmental organizations, and the guerrilla’s military structure ensured a continual flow of information concerning useful activities” (190).

One of the more impressive aspects of campesino organizations in contested regions was that they helped “overcome the demobilizing effects of the repression that swept through their communities” (208). They helped break “the sense of inevitability and inertia experienced during periods of extreme repression” (207). They helped break the hegemony of the inevitable.

Wood concludes:

My interviews with campesinos as well as the patterns of mobilization convince me that there were three reasons that participants supported the mobilization and insurgency, which I will term participation, defiance, and pleasure of agency. In addition, two contingent, path-dependent aspects of the civil war –local past patterns of violence and proximity to insurgent forces – also shaped participation in the insurgency. All concern local processes of the civil war, and all emerged during the course of the civil war and its antecedent mobilization. My account of campesino insurgency also concerns campesinos evolving beliefs about local constraints and opportunities, including likely outcomes, and cultural practices. (231)

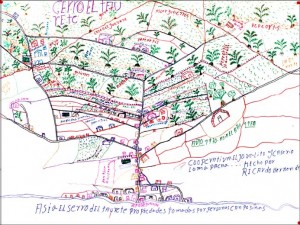

A final word: Wood makes really interesting use of maps in her study. She asked farming cooperatives to draw two maps of the places they inhabited—a pre-war map of the landscape and of the post-war landscape. (Color versions of those maps are available online.) The maps, which are presented at several points in the book, are particularly revealing aids for showing the campesinos’ own political conceptions of changes wrought in and through the symbolic and material landscapes produced by the war.