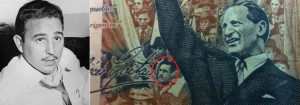

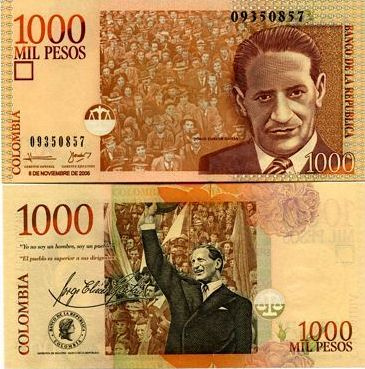

I couldn’t pass this up. It turns out that the artist commissioned to design Colombia’s 1,000-peso bill slyly included a portrait of a young Fidel Castro in the background of the bill. It took eight years for anyone to notice the portrait of the Cuban revolutionary on what I assume, being the smallest denomination, is the nation’s most-circulated bill. The bill glorifies Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, a rising and left-leaning politician from the 1940s, whose assassination on April 9, 1948, symbolically marks for many the beginning of the country’s most recent cycles of violence. (In fact, this year, Colombia will be commemorating the first “National Day of the Victim” and April 9 was chosen for this reason.) When Gaitán was gunned down in the broad daylight of downtown Bogotá, a national uprising emanated from the capital city, and the day is since known as the Bogotazo. Visiting the city that day was Fidel Castro, a 21-year-old Cuban law student who was taking part in a Latin American Youth counter-summit to a meeting of the precursor to the Organization of American States (OAS)—a body from which Cuba remains banned since 1962 at U.S. insistence. The Bogotazo helped further politicize the young Castro, who 11 years later would march victoriously into Havana. José Antonio Suárez, the artist commissioned to design the 1,000-peso note, subversively recorded this historical circumstance on the bill.

Authors like Benedict Anderson and Manu Goswami—and probably others who have written a lot about nationalism—have noted the importance of currency in making nationhood imaginable. Bills usually contain founding fathers (yes, males) and other figures or monuments aimed at drumming up patriotic allegiance and a whitewashed historical narrative. Another common motif, interestingly, is nature or idyllic country settings of the imagined past, or what Raymond Craib calls in reference to maps, “primordial landscapes.” (When was the last time you saw a city skyline on a bill?) Obviously, all the elements are there to both conjure and naturalize the nation spatially and historically. Indeed, one could do for currency the same keen decipherment that Craib did for the elaborate cartouche insets of early Mexican maps.

The 1,000-peso bill, worth about 50 U.S. cents, has a portrait of Gaitán against a backdrop of the masses on one side. On the other side is Gaitán striking a pose backed by a street demonstration, banners waving in the air. Next to his armpit is the image’s second-most visible face on the entire bill: Fidel.

Having a famous Cuban on a Colombian bill will probably be deemed unacceptable by Colombia’s conservative establishment—even more so considering it’s Fidel Castro. Although admitting the resemblance, the director of Colombia’s Bank of the Republic would neither confirm nor deny Castro is on the bill, responding that only the artist would know for sure. He seemed to be taking things in stride: “The artist had total freedom for doing the design. It wouldn’t be right for the Bank to then come in a tell the winner [of the commission] to make a change.”

Today, coincidentally (?), the Bank announced it’s phasing out the 1000-peso bill, which will be replaced by a coin. Poor Fidel.

The artist just denied that it’s Fidel on the bill.