Quinn Norton, a writer with Wired, has published a fascinating three-part series titled, “Anonymous: Beyond the Mask” (Part I, Part II, Part III). She tracks the progressive politicization of Anonymous from its diaper days chatting on 4Chan to #Occupy by way of “ultra-coordinated motherfuckery,” Scientology, Wikileaks, and Tunisia. But, really, it’s all about the Lulz. Seriously. But before getting to the lulz, what is Anonymous? Norton explains that more than anything else Anonymous is a culture—a culture of consummate tricksters. Riffing off of Anonymous researcher Biella Coleman, Norton writes, “The trickster isn’t the good guy or the bad guy, it’s the character that exposes contradictions, initiates change and moves the plot forward. One minute, the loving and heroic trickster is saving civilization. A few minutes later the same trickster is cruel, kicking your ass and eating babies as a snack.” At this blog, we obviously love this. But is lulz a transitional demand?

Quinn Norton, a writer with Wired, has published a fascinating three-part series titled, “Anonymous: Beyond the Mask” (Part I, Part II, Part III). She tracks the progressive politicization of Anonymous from its diaper days chatting on 4Chan to #Occupy by way of “ultra-coordinated motherfuckery,” Scientology, Wikileaks, and Tunisia. But, really, it’s all about the Lulz. Seriously. But before getting to the lulz, what is Anonymous? Norton explains that more than anything else Anonymous is a culture—a culture of consummate tricksters. Riffing off of Anonymous researcher Biella Coleman, Norton writes, “The trickster isn’t the good guy or the bad guy, it’s the character that exposes contradictions, initiates change and moves the plot forward. One minute, the loving and heroic trickster is saving civilization. A few minutes later the same trickster is cruel, kicking your ass and eating babies as a snack.” At this blog, we obviously love this. But is lulz a transitional demand?

“Lulz” comes close to an internet embodiment of the Situationist idea of détournement. It’s tempting to paste Quinn’s entire article—I would recommend at least reading Part I—but here’s how she defines lulz:

The lulz (a corruption of LOL, online shorthand for laugh out loud) is the most important and abstract thing to understand about Anonymous, and perhaps the internet itself. The lulz is laughing instead of screaming. It’s a laughter of embarrassment and separation. It’s schadenfreude. It’s not the anesthetic humor that makes days go by easier, it’s humor that heightens contradictions. The lulz is laughter with pain in it. It forces you to consider injustice and hypocrisy, whichever side of it you are on in that moment.

Anonymous began doing things—and still does—for the lulz, but Norton claims the faceless motley crew has gone from meme factory, specializing in cats, to political prankster, some might say activist. (Most recently, Anonymous took down the FBI’s website and host of others for the punitive shutdown of file hosting site, Megaupload.) Of course, and more importantly, Anonymous is still in the vanguard of cat image-humor.

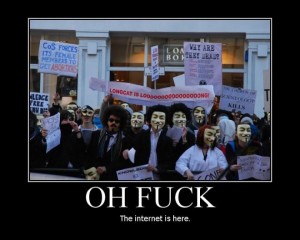

We can thank Tom Cruise and Scientology for bringing Anonymous into its political coming of age in early 2008. When a video of Cruise showing his bat-shit “dedication” to Scientology went viral, the “Church” (or “Buttchurch,” as anons call it) tried to shut it down, threating sites hosting the video. Anonymous retaliated by launching “Project Chanology” with what Norton calls its typical agro-humor. But the lulzy op against Scientology began gaining much more serious traction, even to the point of actual bodies-on-the-street protests (a.k.a. in “meatspace”) at Scientology outposts around the world—not, of course, without a dose of cat-loving lulz (cf. Longcat is Loooooong). For the first time, Anonymous-linked protestors appeared in Guy Fawkes masks en masse (like in V for Vendetta). The era of collective action had dawned on Anonymous.

We can thank Tom Cruise and Scientology for bringing Anonymous into its political coming of age in early 2008. When a video of Cruise showing his bat-shit “dedication” to Scientology went viral, the “Church” (or “Buttchurch,” as anons call it) tried to shut it down, threating sites hosting the video. Anonymous retaliated by launching “Project Chanology” with what Norton calls its typical agro-humor. But the lulzy op against Scientology began gaining much more serious traction, even to the point of actual bodies-on-the-street protests (a.k.a. in “meatspace”) at Scientology outposts around the world—not, of course, without a dose of cat-loving lulz (cf. Longcat is Loooooong). For the first time, Anonymous-linked protestors appeared in Guy Fawkes masks en masse (like in V for Vendetta). The era of collective action had dawned on Anonymous.

Anonymous began taking on more serious foes, radicalizing with every Internet censorship-incited encounter. The Ak-47 of Anonymous is the hilariously named “Low Orbit Ion Canon” (LOIC), which is a software or script used to overload a targeted website, crashing its servers—or what’s called a designated denial of service (DoS) attack. The tactic of DoSing has been used in its various ops: Operation Titstorm, Operation Payback, Operation Avenge Assange, etc. Adrian Crenshaw has a review of these ops, with videos, while describing the non-group groupyness of Anonymous and its actions.

Norton’s series concludes with an interesting review of Anonymous’ actions in the Arab Spring and #Occupy. Generalizing, she notes, “Anonymous [has become] bolder, stranger, more threatening, and more comforting in turns. Last year, Anonymous, like the Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street, picked a fight with the systems of society.”

Norton’s series concludes with an interesting review of Anonymous’ actions in the Arab Spring and #Occupy. Generalizing, she notes, “Anonymous [has become] bolder, stranger, more threatening, and more comforting in turns. Last year, Anonymous, like the Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street, picked a fight with the systems of society.”

Norton traces how the affinities between Occupy Wall Street and Anonymous emerged organically, claiming:

Not all anons support OWS. But many anons said to me when I would talk about Anonymous and OWS: “Same thing.” — not paraphrasing a shared idea — but those exact two words — “Same thing.” After September most of the activist energy of Anonymous seemed to be swallowed by Occupy.

With the latest crackdown against Megaupload for online “piracy,” Anonymous shot back with a LOIC blast against a raft of sites: justice.gov, RIAA.com and MPAA.com. Unlike other LOIC attacks this one was modified in a way that mobilized users computers without their knowledge if they unwittingly clicked on a link. This new tactic drew criticism from outsiders and even many anons themselves. And yet, though ethically suspect, as Norton notes in a post discussing the attacks, the tactic may have made it harder for authorities to prove anyone directed the LOIC intentionally. In other words, each and all may have been protected from prosecution because of the nature of anonymity and ubiquity provided by the collective action.

More reading:

Biella Coleman: “Anonymous: From Lulz to Collective Action,” The New Everyday

Biella Coleman: “Hacker Politics and Publics,” Public Culture

Adrian Crenshaw: “Crude, Inconsistent Threat: Understanding Anonymous,” Iron Geek

A brief history of Anonymous, a short video Documentary produced by Wired based on Norton’s reporting:

Pingback: Interweb Motley # 17 | Territorial Masquerades