This post discusses some scattered points raised about violence by Hannah Arendt’s On Violence, Walter Benjamin’s “Critique of Violence,” and Michel Foucault’s Society Must be Defended. Arendt makes a worthwhile distinction between power and violence, while recognizing that the two rarely operate in isolation of each other (50, 52). “Nothing, as we shall see, is more common than the combination of violence and power, nothing less frequent than to find them in their pure and therefore extreme form” (46-47). Taking her definitions of power and violence into account, we can conclude that violence, for Arendt, is almost always something wielded “in concert”—that is, collectively.

This post discusses some scattered points raised about violence by Hannah Arendt’s On Violence, Walter Benjamin’s “Critique of Violence,” and Michel Foucault’s Society Must be Defended. Arendt makes a worthwhile distinction between power and violence, while recognizing that the two rarely operate in isolation of each other (50, 52). “Nothing, as we shall see, is more common than the combination of violence and power, nothing less frequent than to find them in their pure and therefore extreme form” (46-47). Taking her definitions of power and violence into account, we can conclude that violence, for Arendt, is almost always something wielded “in concert”—that is, collectively.

Without directly coming to terms with it, the “collectivity” being hailed by Arendt in her discussions on how power and violence intersect is the state. She argues that unchecked violence cannibalizes power, meaning that violence’s fuel is the withering away of state power. This contention comes through strongest in her definition of terror, which she describes as rule by absolute (i.e. powerless) violence and its inherent social atomization (everyone’s a potential snitch/informant). Weak states—or weakly supported states—are violent states. This framework rings somewhat hollow through the lens of fascist Italy that Antonio Gramsci sought to come to terms with; it’s also at a loss for addressing Pierre Bourdieu’s symbolic violence in which power is practically a precondition.

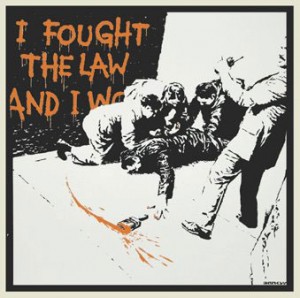

Arendt’s attempt to parse violence and power is an important one, but her view becomes rather clunky when considering the differential violent treatment of populations internal to the body politic. Foucault’s analysis of war and “race war” in the emergence of biopolitics seems a much more adequate way of tracing the relationship between violence and power—both on an individual and collective level—whether it’s through making live and letting die (biopower) or taking life and letting live (sovereignty). Benjamin’s “Critique of Violence” takes on the state in a much more direct way than Arendt does, though less so than Foucault. Foucault, who earlier in the book acknowledges the blood “dried on the codes,” would have approved of Benjamin’s point that “it may be readily supposed that where the highest violence, that over life and death, occurs in the legal system, the origins of law jut manifestly and fearsomely into existence” (242). Benjamin is not only pointing out the constitutive and ongoing splatter of blood on the codes—i.e. lawmaking and law-preserving violence—but also the way in which the law itself is upheld through a distinction between sanctioned and unsanctioned violence; even though he argues that all violence is ultimately lawmaking.

Arendt’s attempt to parse violence and power is an important one, but her view becomes rather clunky when considering the differential violent treatment of populations internal to the body politic. Foucault’s analysis of war and “race war” in the emergence of biopolitics seems a much more adequate way of tracing the relationship between violence and power—both on an individual and collective level—whether it’s through making live and letting die (biopower) or taking life and letting live (sovereignty). Benjamin’s “Critique of Violence” takes on the state in a much more direct way than Arendt does, though less so than Foucault. Foucault, who earlier in the book acknowledges the blood “dried on the codes,” would have approved of Benjamin’s point that “it may be readily supposed that where the highest violence, that over life and death, occurs in the legal system, the origins of law jut manifestly and fearsomely into existence” (242). Benjamin is not only pointing out the constitutive and ongoing splatter of blood on the codes—i.e. lawmaking and law-preserving violence—but also the way in which the law itself is upheld through a distinction between sanctioned and unsanctioned violence; even though he argues that all violence is ultimately lawmaking.

The state is in a fundamentally fragile and unstable position in Benjamin’s critique: Legally constituted and preserved by violence, while desperately trying to bracket individual violence that poses an existential threat to the legal order (i.e. the state) itself. The bracketing of non-sanctioned violence, Benajamin notes, does not stem so much from the nefarious ends that this kind of violence might pursue, but rather from the threat it poses to the law itself by virtue of flaunting the law and, thereby, the state (a similar point is also made by Carl Schmitt). The “Great Criminal” (the outlaw as folk hero), interestingly, appears in both Benjamin and Foucault—somewhat in Arendt, too—probably because of how much such figures can tell us about the fragile ties between law, power, and violence in relation to social justice, all central themes to these texts. Finally, using Sorel’s distinction between the political strike and the proletarian general strike, Benjamin calls the latter “pure means” and “non-violent,” precisely because of its waging of no demands, meaning it skirts a means-end calculus and is beyond the purview of the law and its violent entrapments.

Agamben seems to side with Arendt and Benjamin over Foucault. But Agamben also appears not to have read Foucault’s last few seminars, at least when he was writing Homo Sacer.

16 Lakewood Dr, Vancouver, BC